Continued (page 2 of 3)

The museum’s five curators compiled a list of countries and instruments, and then the curators along with more than 130 consultants traveled the world, procuring instruments as well as the audio-visual footage Bob desired. The Asian curator had to backpack through jungles to obtain her footage. Now there are more than 10,000 instruments in the museum’s exhibition and research collection; 3,000 are on display.

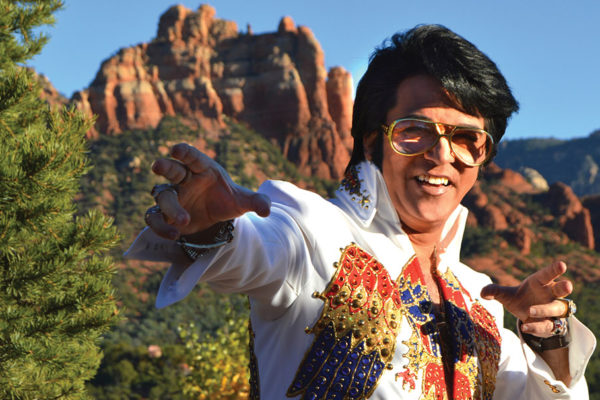

Bob spends most of his time at his home in Minneapolis, and Bill, who has a Ph.D. in cultural anthropology, heralds from Pittsburgh, where he was the director of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History for six years. Why is MIM located in the middle of the Sonoran desert? “It was a strategic decision,” says Bill. “Why not Phoenix? It’s a rapidly growing metropolitan area that’s close to two of the most important tourist attractions: Los Angeles and Las Vegas. It’s also close to one of the seven natural wonders of the world – the Grand Canyon. It has a large residential population and people who travel for conventions and resorts as well as international visitors coming to see our natural attractions. It was an opportunity to capture all markets.”

While that’s certainly true, it’s obvious that MIM also doesn’t have nearly the competition that it would have in a more cosmopolitan city. While we love the Heard Museum, the Phoenix Art Museum and the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, they are all much smaller – and much older – than MIM. And we haven’t seen anything in this state that compares to the museum’s audio-visual component. The sophisticated museum shop and gourmet (and affordable) café don’t hurt, either.

Galleries

It’s easy to spend hours wandering through MIM’s galleries. In addition to the world-music exhibits, you’ll also find the Orientation Gallery; Mechanical Music Gallery, which includes the museum’s largest and most expensive instrument, a 37-foot-wide dancehall organ from Belgium; the Experience Gallery, where you can actually “bang a gong”; the Target Gallery, which features traveling and temporary exhibits; and the Artist Gallery, one of our personal favorites. It was there we marveled at John Lennon’s 1969 Steinway & Sons piano on which he composed “Imagine”; the 1956 Stratocaster – nicknamed “Brownie” – that led to Eric Clapton’s “Layla” and “Bell Bottom Blues”; and the first Steinway piano ever made, from way back in 1836.

“We don’t have as much rock ’n’ roll as other museums because we wanted to make sure what you get at MIM you’re not getting anywhere else,” says Christina Linsenmeyer, assistant curator of musical instruments. Christina, who began working at MIM in October 2008 when she was a doctoral candidate at Washington University in St. Louis and who is also a violin maker, was one of the curators who helped assemble the museum’s collection. Her beat: Western Europe.

Christina led us across a foyer featuring a mosaic map of the world and upstairs via a spiral staircase into the United States-Canada gallery. She pointed out the fact that the Native American exhibit at MIM has the largest square footage of Native American instruments on display in the world. Christina says that isn’t the only thing that sets MIM apart. First, it contrasts the old and new. “One of the things I am most proud of are all the aspects of MIM that haven’t been done to date,” she says. “We show instruments made by musicians who are not professional instrument makers, which means the craftsmanship isn’t what you would expect. You’ll also find instruments that are over 50 years old right next to instruments that come straight from the makers and are unaltered. Sometimes those are the most exciting.”

MIM also exhibits acoustic and electric instruments side by side, something that is nontraditional in the realm of music museums. It also exhibits instruments in ensembles, to give visitors an idea of who was playing what and when. In an exhibit, you’re just as likely to see traditional costumes displayed with the instruments. “Our challenge was what story we wanted to tell with each country,” says Christina. “This isn’t about the history of music, though that does come across. We use the objects to hang stories on. We lean toward the everyday, so you’re not just seeing the study of folk music but also folk traditions.”