Continued (page 4 of 5)

“Sedona is naturally a dark sky site primarily due to its size,” he says. “We only have 10,000 people living here and we are relatively remote. We also have more clear nights than locations like Flagstaff that get hit more frequently with summer and winter storms.”

Evening Sky Tours hosted its first community stargazing event at Sedona Red Rock H.S. in June, followed by a meteor shower camp-out in August. At press time, Cliff said he was working on a Mars party for October and hoped to establish a star party in Sedona that will draw amateur astronomers from all over the world to town with their telescopes. He says those attending sky tours always want to see shooting stars while Jupiter and Saturn never fail to capture the imagination. This past summer, guests at a private star party were able to watch the space shuttle through a telescope, a rare treat.

“It’s important to talk to people about what they are seeing when they look through a telescope,” says Cliff. “Essentially, you are looking back in time. When we look at a star 11 million light years away, we are looking 11 million years back in time.”

For information on Evening Sky Tours, call 928-203-0006 or visit www.eveningskytours.com.

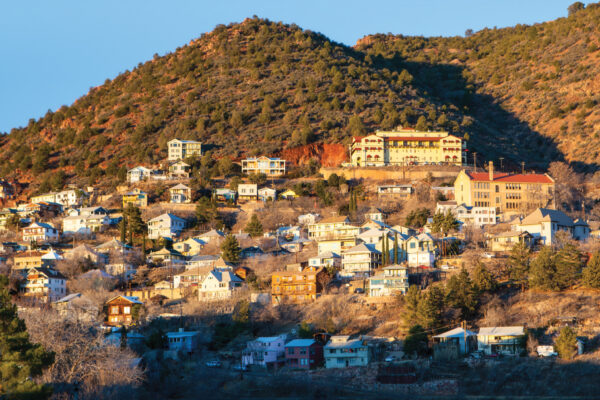

Lowell Observatory

Sitting atop Mars Hill, just minutes from downtown Flagstaff, sits Lowell Observatory, one of northern Arizona’s gems. The private, non-profit research institution was founded in 1894 by Boston-born Percival Lowell but is best known for the 1930 discovery of Pluto. The observatory’s original 24-inch Alvan Clark telescope – built in 1896 to study Mars – along with a museum, science center, and space theatre are open to the public daily and many evenings, especially in summer.

“We have about 70,000 visitors every year,” says spokesman Steele Wotkyns. “We have 20 full-time astronomers and we’re the oldest education institute in Flagstaff.”

Lowell offers guided tours during the day, giving visitors a fascinating look at the Clark telescope, housed in a wooden dome that rotates on 1954 Ford truck tires. Behind it sits the old wooden chair where Percival Lowell spent many hours looking at Mars and searching for “Planet X” until he passed away in 1916 (he’s buried outside the Clark observatory). His staff kept up the search and, in 1930, Clyde Tombaugh found the ninth “planet” using a different telescope, also part of the observatory tour. When asked whether he believes Pluto to be a planet or a “dwarf planet,” as it’s been newly classified, outreach manager Kevin Schindler laughs.

“By traditional definition, it’s a planet,” he says. “But it was also thought at first that asteroids were planets until [the realization] they were a different type of celestial body. Pluto could be a prototype. But [either way], it gets people talking about astronomy and that’s what’s important.”

Just don’t ask Kevin if Pluto was named after the lovable Disney dog that made his debut the same year. Venetia Burney, an 11-year-old girl from England, won a naming contest – she was learning about Roman mythology in school at the time (she’s alive and still sends Christmas cards to the observatory). Kevin says Walt Disney was fascinated by space and adds – planet or dwarf planet – Pluto was the cartoon dog’s namesake.

Yet Kevin and Steele say the observatory may have made even greater discoveries than Pluto. Between 1912 and 1914, V.M. Slipher made discoveries leading to the realization that our universe is expanding – the instrument he used and more about the expansion are on display at the observatory. The rings of Uranus, the three largest known stars, oxygen on one of Jupiter’s moons and gyrochronology – a means of determining the age of a star – were all discovered at Lowell. Today researchers focus on asteroids and near-Earth objects, planets orbiting other stars, and the brightness stability of the sun.